Variations

January 27 - March 3, 2012

Beta pictoris gallery, Birmingham, Alabama

Essay by Hesse McGraw

We learned from Big Love that sister-wives in plural marriage must love each other. Republican presidential candidate Newt Gingrich has just railed against the “destructive, vicious, negative … news media” for its interest in his second wife’s claims that Newt desired open marriage. Current piety notwithstanding, Newt had a pretty hard time with Bill Clinton’s infidelities back in the 90s. Much of our world is a posture game: ourselves against the other, the world within us.

In contemporary America, our political landscape is defined by continual staking of the middle ground — We are normal America, We are the 99% — an essentializing of average values against the marginal, foreign and Other. Attempts to define the contemporary world in such monogamous terms — there is one ideal, and it’s like me — of course fail, and disregard the hyper-plurality we all contain.

Matt Wycoff has rather sought to highlight his own subjectivities and pursued open marriage within his own work. His artistic practice is compelled to cheat, or is perhaps more akin to plural marriage — despite difference, his factions have each other’s back. This promiscuity is unabashed in its freedom of form. The liberty of his artistic practice is not in knowing what you want, but knowing you want something else.

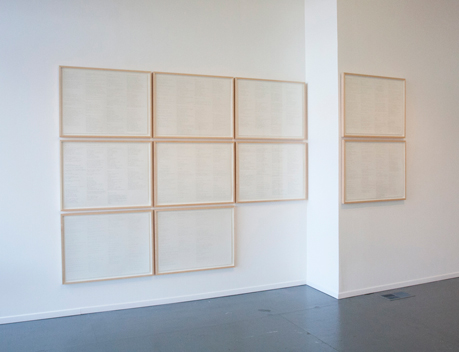

In his work from 2004 to approximately 2007, Wycoff relentlessly made literal the margins of his self. These honest-to-goodness works, whose titles were adamantly descriptive — Survey of disaster, war and death during the first 25 years of my life (1980-2005), Everyone whose name I know but have never met, Everyone I've ever met, Everywhere I've ever been, Re-enactment of my first intoxication, Re-enactment of the loss of my virginity, Re-enactment of my expulsion from eighth grade, Everyone I've ever met who has died, Every word in the English language that I don't know — are diaristic, without being self-obsessed. They speak to the simultaneous completeness and incompleteness of the individual. In other words, they defined the impossibility of normalcy.

This work compressed the distance between personal experience and fundamental human concepts such as death, knowledge, fame, memory, language, and humor. While moving fluidly between drawings, photographs and graphed information, Wycoff built a quietly welcoming platform atop his own direct experience of language, death, and the world, where viewers could reflect upon their understanding of these universal spaces.

A pivotal work from 2007, Color field paintings loosely inspired by color I see during orgasm 1 – 4, shifted Wycoff’s common ground between the self and “everything else.” Here, he seemed to recognize the cataloguing, reenactments and truth-telling of previous works stopped short, precluding mystery, the unknown and a personal uncanny. These large color fields, vignetted hazes of chrome yellow, clear blue, translucent green and an odd orange, assumed the epic scale of previous works such as Every word… yet added the shroud of doubt, and a kind of speculative jolt. Why don’t I see those colors?!

Earlier works removed shrouds, such as Every secret I’ve never told (2005), and the reveal was painful, if difficult to believe. These works tested one’s belief in the soul-bearing and exhaustive capacity of the work; would he uncover everything, what would remain concealed? In this play in the limits of self and its edges with the other, there remained a fully contingent fact — the work rewards a sympathetic viewer. For one to believe the weight of an exposed secret, another must be kept. To cringe at the awkwardness of Wycoff’s reenactment of his first sexual experience with his original partner, one must share similar distance to their own experience.

Much of this work sought to index totalities, and that posture revealed borderlands between personal and universal structures, subjective and elastic histories. For Wycoff, however, the approach contained inherent limits. It was monogamous to direct experience.

The work rippled in 2007. With remarkable attention to form, new directions followed the strict grids of earlier works — poems, then anagrams of canonical texts that scrambled their meaning, then askance geometric forms, which questioned their support, frame and modes of presentation.

Wycoff's paintings and sculptures of 2009 and 2010 gauge the ability of iterative abstraction to provide an index for personal and collective histories. Work such as Signals 2 are off-kilter and spectral, they are direct, and elusive. These works assert abstract painting as a place for earnestness, but also a place for self-doubt, a place to work things out without the urgency of an expressive agenda.

Wycoff wrote recently of the multi-directional nature of his work, “the results of this lateral movement are artworks that seem more aware, closer to embodying the contradictions that enable them, and more conscious of the repercussions that flow from them. As such, they approach what is an ultimately uniterable confluence of cause and effect — the incomprehensible center to which language and reason are drawn but can only orbit.”1His incomprehensible center is the potent core of these variations.

Through these shifts, Wycoff seemed to ask ‘Is this work doing what it’s supposed to do?’ ‘Do I have the right relationship with this work?’ ‘What are the other relationships I could have?’ The binary arrangement of information in previous works: knowledge/gap, dead/living, which were rigorous and contingent on an implied truth, gave way to inferred possibilities. Ultimately in pursuit of uncertain directions, of the incomprehensible center, there is grounding in the process, in the doing, but also in the question ‘Where am I in this work?’

Whereas earlier works were interested in fixing the self within a field of information, of literally mapping his place in the world, Wycoff’s newest work opens a terrain of non-fixed information. This is a non-place for which there is no index, yet fully occupy-able.

This work carves new ways out of the same problem, the impossibility of understanding one’s place in the world. In the essay Painting as History, Wycoff writes “For individuality to be prefaced in this manner by the other is to begin to construct individuality as porous and dependent rather than primarily rights based and autonomous.”2 This porosity flows through insouciant works such as Untitled (2011), a veiled 100 x 88” canvas that airs so much, yet leaves room for discovery. Critic Sharon Butler referred to this state as one of “no clear truth or falseness,” a cause one might find both hopeful and ambivalent.3 In Wycoff’s case, arrival here, a place of openness and unexpected possibility, is the beginning of a grander project, an abandon to the unknown.

1 Matt Wycoff, “Painting as History, 2010,” Accessed at www.mattwycoff.com (2010).

2 ibid.

3Sharon L. Butler, “Abstract Painting: The New Casualists,” The Brooklyn Rail (June 2011).

Hesse McGraw is a curator, writer and artist working as curator at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska. He was the founding director and curator of Paragraph, a contemporary art gallery operating under the non-profit Urban Culture Project in downtown Kansas City, Missouri. He is the former assistant director of Max Protetch gallery in New York, City and former senior editor of Review, a Kansas City-based visual culture magazine.